Recently there has been some good writing done about race in Southeast Asia. Before this, most of the history that dealt with race was pretty influenced by Eurocentric ideas or nationalist narratives that supported a particular race’s “uniqueness.” But this new stuff is pretty, so here is a little intro to the newer ideas floating around out there.

In Southeast Asian historiography, the construction of racial knowledge has largely revolved around and evolved from European ideas of race, nationalism, and coloniality. From John Sydenham Furnivall’s notions of a “plural society” to more recent “clash of cultures” theories, thinking on the racialization of the Southeast Asian body and state has been fairly limited. However, recent work by a number of scholars in fields such as history, anthropology, and sociology are begging to challenge these older understandings. These authors seek to reevaluate the place of race in daily practice, the formation of modern postcolonial states, and even see implications for transnational race formation that occurred between colonizers and the colonized.

Charles Hirschman’s article, “The Making of Race in Colonial Malaya: Political Economy and Racial Ideology,” Sociological Forum, 1, No.2 (Spring, 1986): 330-361, is a great starting point for this project as he seeks to demonstrate that what we now identify as discrete racial groups in Southeast Asia are in fact legacies of imperial structures from the colonial period. He uses the case of “race relations” in Malaysia to argue that “direct colonial rule” created these racial “byproducts” as a result of classification, stratification, and labor-based exploitation of the colonial subject. While Hirschman acknowledges that pre-modern Southeast Asia was a world of “ethnocentrism,” he argues that the “racial ideology of inherent difference” was a European import. Western ideas of the “lazy Malay,” entrepreneurial Chinese, and the willing Indian laborer caused a “qualitative shift” in the economy and society which hardened local understandings of race.

These stereotypical ideas of racial differentiation were not merely a popular understanding or a natural outcome of transforming means of production, but rather, according to Daniel P.S. Goh’s article “States and Ethnography: Colonialism, Resistance, and Cultural Transcriptions in Malaya and the Philippines, 1890s-1930s,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 49, No.1 (2007):109-142, these differences were created as part of a colonial logic which combined scientific racism and social Darwinism to “make legible” the colonial subject and create systems of knowledge and control. Here Goh argues that the “transcription” of local peoples, knowledge, and methods of resistance allowed colonial officer-ethnographers to debate native peoples’ level of civilization on a sliding scale from “degenerated medievals” which were currently incapable of progress to “model medievals” nearly in line with Europe’s past. While this model employed by late nineteenth century ethnographers did in theory allow for the possibility of progress, in also froze different races in pre-modern time based on cultural differentiation or resistance to white rule and allowed white Europeans domination of racial distinction and classification within the colonies.

This idea that “white” imperialists brought racial classifications to Southeast Asia and implemented power structures based on the production of the social economy or ethnographic knowledge is challenged by Paul Kramer’s article “Empires, Exceptions, and Anglo-Saxons: Race and Rule between the British and United States Empires, 1880-1910,” The Journal of American History, 88, No.4 (Mar., 2002), 1315-1353, which seeks to demonstrate that some of the idea of whiteness, or more precisely Anglo-Saxonism” were created in the colonial world and not in the metropole. Kramer argues that the American and British empires shared an “inter colonial” production of “Anglo-Saxon” racial exceptionalism that was created in the empire itself. Rather than bringing hard, pre-formulated notions of race to the Philippines and Malaysia, Kramer demonstrates that these ideas of racial superiority were partially crafted in transnational peripheries to support, organize, and legitimize empire. Anglo-Saxon identities thus were created “in relation to empire.”

But if Anglo-Saxons could create racial identities in relation to empire, surely colonial subjects in transnational social systems and economic flows could do likewise. Chua Ai Lin’s article “Nation, Race, and Language: Discussing Transnational Identities in Colonial Singapore, Circa 1930” Modern Asian Studies, 46, Special Issue 2 (March 2012): 283-302, explains that just as white racial identity was formed in transnational spaces, racial knowledge of Indian and Chinese Malays were created in a complex mix of local and global influences. As British subjects living in Malaya with ties to familial origins in India or China, these “non-Malay” people utilized notions of language, citizenship, and place in their own logics of race. Primarily concerned with maintaining their identity as “Straits Chinese” and Malay Indians, Lin tells us that these people simultaneously embraced British subjecthood and “gained pride” from the “rising international status of India and China.” Again, this process can be seen as creating harder and clearer cut racial identities where previously other forms of social knowledge and representation existed.

These sharp distinctions in race formation, knowledge, and self-identification would outlive the colonial period and, in many ways, come to define the parameters of race and nationalism in postcolonial Southeast Asian nations. Daniel P.S. Goh’s article “From Colonial Pluralism to Postcolonial Multiculturalism: Race, State Formation and the Question of Cultural Diversity in Malaysia and Singapore” Sociology Compass, 2, No.1 (2008): 232-252, takes up this issue and argues that unlike “postimperial societies,” postcolonial societies “built on colonial racialization” came to view race as integral to nationalism thus creating a societies in which “multiculturalism” was a problematic “fact”; a “dilemma to be dealt with from the beginning of nation building.”

While all of these articles add new ideas and ask a series of interesting questions, they also seem to share a common set of problems. Partially based on their foucauldian analytic methods, they seem to attribute tremendous power to the state and focus away from individual response, reason, and (ir)rationality. Moreover, as these authors seek to sidestep American and European racialization and observe transnational Southeast Asian constructions of race (even the Anglo-Saxon ones) they rely only on English-language discourse and primary sources. Also, some of the authors’ ideas of race fall apart in the light of comparison to say the American Civil War, Jim Crow laws, and continuing forms of racial differentiation often referred to under the contemporary euphemism of “development.” Any compelling notions of race and race production in Southeast Asia must contain these comparative models and ask broader questions. How did Japanese technological progress and claims to be “white” affect the racial ideology of other Asians? How did American, Dutch, and British racism vary and did this have an effect especially on the peripheries of empire? How might America’s internal “decolonization” of black peoples and communities compare to decolonization in postwar Southeast Asia? Such questions combined with a greater use of local sources in non-English-language sources would surely expand the field and produce new and interesting theories and knowledge.

When I was a kid, one of my favorite late-night rerun television shows was M*A*S*H, a long running series about a mobile army surgical hospital during the Korean War. The TV series was based on the 1970 film by the same title which was itself based on a 1968 book entitled MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors.

When I was a kid, one of my favorite late-night rerun television shows was M*A*S*H, a long running series about a mobile army surgical hospital during the Korean War. The TV series was based on the 1970 film by the same title which was itself based on a 1968 book entitled MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors. As it became a movie and then a television series, the narrative became a clear critique of the Vietnam War. The TV series in particular portrayed the United States Army as largely consisting of incompetent buffoons at the top and generally liberal people at the bottom. In the early years of the TV show which began broadcasting in 1972, there were a number of errors such as suggesting that Korea was part of Southeast Asia, or looking for communists/comrades in the jungle that hinted at the association of the series with events in Vietnam. In many ways, MASH can be seen as part of a television phenomenon that changed American attitudes during the prolonged war. Some critics even accused the show’s writers of have damaged American moral and helping America “lose the war on television.”

As it became a movie and then a television series, the narrative became a clear critique of the Vietnam War. The TV series in particular portrayed the United States Army as largely consisting of incompetent buffoons at the top and generally liberal people at the bottom. In the early years of the TV show which began broadcasting in 1972, there were a number of errors such as suggesting that Korea was part of Southeast Asia, or looking for communists/comrades in the jungle that hinted at the association of the series with events in Vietnam. In many ways, MASH can be seen as part of a television phenomenon that changed American attitudes during the prolonged war. Some critics even accused the show’s writers of have damaged American moral and helping America “lose the war on television.” Well, this might not be as straight forward as those critics thought. As it turns out, Larry Gelbart, one of the main comedy writers for the show had, only five or six years earlier, been using television to help America win the war in South Vietnam.

Well, this might not be as straight forward as those critics thought. As it turns out, Larry Gelbart, one of the main comedy writers for the show had, only five or six years earlier, been using television to help America win the war in South Vietnam. In 1966, the United States Information Agency decided to bring television to South Vietnam both to entertain American troops and make gains in their propaganda efforts. The USIS brought in thousands of television set, primarily from Japan, and helped the South Vietnamese government make their own TV station. Filming and programing began in Saigon at the National Film Studio (“national” might be a bit of a misnomer as it was actually endorsed and run by the USIS utilizing Filipino cameramen, crew, and directors, but that is a story for another time). Larry Gelbart, along with several other young American television writers and consultants were recruited to come to Saigon and shape this Vietnamese television channel, Truyền hình Việt Nam-TV, into the best state propaganda machine it could be. They dubbed old American war movies in Vietnamese, created newsreels supportive of the South Vietnamese government, and played plenty of old Vietnamese opera films to keep things lively. How well these channels worked to meet the USIS objectives is anybody’s guess.

In 1966, the United States Information Agency decided to bring television to South Vietnam both to entertain American troops and make gains in their propaganda efforts. The USIS brought in thousands of television set, primarily from Japan, and helped the South Vietnamese government make their own TV station. Filming and programing began in Saigon at the National Film Studio (“national” might be a bit of a misnomer as it was actually endorsed and run by the USIS utilizing Filipino cameramen, crew, and directors, but that is a story for another time). Larry Gelbart, along with several other young American television writers and consultants were recruited to come to Saigon and shape this Vietnamese television channel, Truyền hình Việt Nam-TV, into the best state propaganda machine it could be. They dubbed old American war movies in Vietnamese, created newsreels supportive of the South Vietnamese government, and played plenty of old Vietnamese opera films to keep things lively. How well these channels worked to meet the USIS objectives is anybody’s guess.

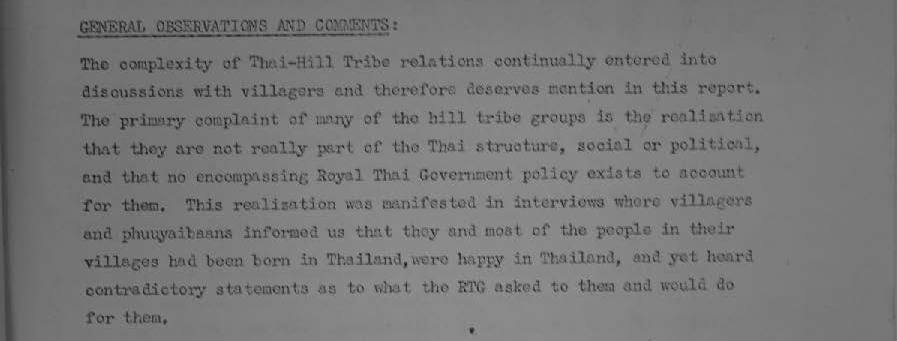

Mae Salong may be my favorite place in Thailand. Not only does it grow and produce wonderful oolong teas in the Taiwanese style, but it is also filled with funky modern history and is more than twenty degrees colder than Bangkok or even neighboring Chiang Rai.

Mae Salong may be my favorite place in Thailand. Not only does it grow and produce wonderful oolong teas in the Taiwanese style, but it is also filled with funky modern history and is more than twenty degrees colder than Bangkok or even neighboring Chiang Rai.